Regulations, Abundance, + Attainability

- Charlotte Dhaya

- Dec 11, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: 3 days ago

Authors: Eric Kronberg, Elizabeth Williams, AICP, LEED AP, RA

Editors: Charlotte Dhaya, Darby Fly

I. OUR FOUR CORE PRINCIPALS

At KUA, one of our main goals is to figure out pathways to increase an abundance of unsubsidized, attainable, and responsible housing. Let’s break down what we mean by that:

Abundance

We use this term to directly combat the phrase “housing scarcity”. An abundance approach to housing focuses on policies that create more housing supply for more people. Rather than rationing limited attainable units through subsidies (which help some families but leave many others in the cold), an abundance approach aims to lower costs across the board by simply making it legal and feasible to build more housing.

Think of it this way: demand-side subsidies, where governments help people pay for expensive housing, work like a lottery system. They're helpful for the winners, but most people are still stuck with unaffordable options. This limited subsidy also drives up the costs of housing for everyone else. The real solution is increasing supply to meet demand.

Unsubsidized (Federally)

America's housing crisis affects communities of every size, from major cities to small towns. While subsidies are important, they're expensive and limited; We simply can't subsidize our way out of this problem when the core issue is a shortage of available homes. The less subsidy that is needed for units at 80% AMI+ allows for more subsidies to be allocated to those who need it the most. This results in more housing opportunities and more pathways to economic success for communities.

Policy reforms can immediately open up more housing opportunities without requiring taxpayer dollars. Currently, subsidized units typically target households earning 30-80% of Area Median Income (AMI). Specific policy reforms can allow for the creation of more housing, thus reducing or eliminating the need for subsidized housing at attainable price levels (60-80% AMI). This allows developers to place existing subsidies where they are needed most, at below 60% of AMI, creating broader economic opportunities in our communities.

Attainable

We like the word “attainable” because it literally means “feasible”; in this context it simply means housing that is feasible to build and feasible to afford. The term "affordable" has become so loaded with technical definitions that it's become difficult to have clear conversations about what housing costs should actually be in a given community.

Using the phrase "attainable" lets us talk plainly about whether regular families can realistically find housing that fits their budgets, and do so without getting tangled in housing finance terminology.

Responsible

To achieve economic abundance for our families and communities, we must use our land wisely. This means maximizing housing opportunities while protecting jobs, community character, and environmental resources. To build responsibly, we:

Densify existing infrastructure – Building more housing where utilities, roads, and services already exist maximizes the value of past investments

Protect natural resources – Concentrating development reduces sprawl into undeveloped areas, preserving rural lands and open spaces

Reduce transportation costs – Allowing housing near jobs and transit not only helps families save money but also reduces vehicle emissions, a major component of the affordability crisis that often gets overlooked

These four principles guide everything we do. But understanding our approach requires understanding a technical reality that most people outside the development world don't know about: the hidden barrier created by building code thresholds.

II. THE TECHNICAL REALITY: BUILDING CODES VS ATTAINABILITY

Here's where the rubber meets the road. A seemingly minor technical detail, which building code applies to your project, can determine whether attainable housing pencils out or dies on the drawing board. Two building codes govern how we construct housing in America, and the difference between them is dramatic. These are International Residential Code (IRC) and International Building Code (IBC). Both IRC and IBC are comprehensive codes designed for specific building types, differing in the requirements and scope needed.

The International Residential Code (IRC)

At a high level, the IRC is the simpler code. It's designed specifically for:

Single-family homes

Duplexes (AKA two-family residences)

Townhouses

These building types must be three stories or less.

Key IRC advantages:

Prescriptive requirements – The IRC essentially provides a simplified cookbook approach. Follow the recipe, and you're code-compliant. This makes design, permitting, and construction more straightforward and less expensive

Lower construction costs – Simpler requirements mean lower design and engineering costs, which translate into simpler, more cost effective buildings

Faster approval – Less complex plans mean quicker permit review times

Wood-frame construction friendly – The IRC is well-suited to traditional wood-frame building methods that most local contractors know well

Key IRC disadvantage:

Zoning Limitations – Zoning often limits IRC buildings to one home per lot. This typically requires a significant amount of land per unit of housing, wasting precious city resources and driving up the cost of housing. Leveraging the benefits of an IRC focused approach requires a companion approach to infill zoning reform to maximize attainable outcomes.

The International Building Code (IBC)

The IBC is the comprehensive code that applies to everything else:

Apartment buildings with three or more units

Commercial buildings

Mixed-use developments

Institutional buildings

Key IBC characteristics:

Higher design costs – Requires licensed architects, mechanical, electrical, and plumbing structural engineers for most projects

More complex requirements – Fire separation, accessibility, egress, engineered systems—all require detailed design and engineering analysis

Stricter fire safety – Multi-family buildings under IBC require fire sprinklers, fire-rated assemblies, and more robust compartmentalization

Longer approval timelines – More complex plans require more extensive review

Accessibility Requirements – ADA (most uses) and the Fair Housing Act (residential uses) typically apply to these projects

Much higher construction costs – All these increased requirements directly increase the cost of construction of buildings

The IRC/IBC Threshold

The Most Important Threshold in Housing Policy

The three-unit building threshold is a big deal. When a building hits that third unit, it typically crosses from IRC to IBC territory, and costs jump significantly, often by 20-30% or more. This creates a substantial barrier to building "missing middle" housing like small apartment buildings.

Missing middle housing is a popular topic in the attainable housing world, but the increased costs associated with IBC buildings create significant limitations, particularly for communities that need deeper attainability relative to local incomes.

Just a quick technical clarification- townhomes are permitted under the IRC, but they technically consider each unit as a separate building. Building a three unit townhome is typically much simpler than a three unit apartment building, AKA a triplex.

A Note on IBC Infill Housing

While we focus on the benefits of IRC development in this article, IBC buildings play an important role in specific contexts. However, project complexities typically compete with project efficiencies, making financial sense harder to achieve for attainable housing.

We see IBC projects generally requiring a minimum of 20-40 units to pencil financially. Also note that most of our IBC missing middle projects benefit from local subsidies. The challenge: struggling communities that need attainable housing most often require lower rents to meet local income needs. The higher costs associated with IBC development often mean projects need additional subsidy to hit attainability targets, even with smaller units and less parking.

Our perspective

IBC buildings are valuable tools in the right contexts—walkable neighborhoods with good mobility options and available subsidy. But they're not a universal solution. For communities that lack these conditions, IRC development offers a more direct path to attainability.

III: OUR PATHWAY TO SUCCESS

Why IRC Construction is Our North Star for Attainable Ownership

Our North Star is the creation of flourishing communities. Our definition of a successful project is one that contributes toward vibrant, inclusive, and lasting neighborhoods. We tackle projects that provide attainable housing, infill development, and building types that fit their context.

What Outcomes Do We Look For?

Each of our projects focuses on three key outcomes:

Increased community livability – Thoughtfully designed housing that makes neighborhoods better places to live

Creation of contextual housing choices for mixed-income communities – Diverse housing options that serve different people across a range of income levels, with an emphasis on adding attainable option which are typically lacking in many communities

Furthering the economic vibrancy of a community – Housing that supports local businesses, jobs, and tax base

One of our primary pathways to successful attainable home ownership outcomes is IRC infill housing coupled with land use reform. Why? Because providing these types of needed projects are often illegal or deeply infeasible under current zoning regulations. Changing these rules can be daunting for developers and/or elected officials on a case by case basis. Our sister company, Inc Codes is a consulting firm that works with community policy makers to incrementally reform existing codes for maximum impact.

IRC buildings are simpler and easier to build by smaller contractors and can be deployed incrementally when they are legalized. We have six key principals for implementation:

Implementation Principles

Zoning & Subdivision Reform: Remove Unnecessary Barriers

Changing zoning is a key first step to improving housing options and attainability, specifically frontage and lot size flexibility; we utilize small lots to leverage IRC construction. The ability to allow multiple units per individual smaller lot is crucial to being able to leverage the simpler regulations under IRC. Flexible lot sizes mean more housing units can be built more attainably utilizing existing infrastructure.

Small Units: Size Matters for Affordability

The smaller the unit, the more attainable the home becomes. Our projects typically range from 250 SF studios to 1,700 SF four-bedroom homes, with our common unit sizes falling in the 400-1,400 SF range.

Why does this matter? Smaller units cost less to build and less to rent or buy, making them accessible to more households. This isn't about cramming people into tiny spaces—it's about providing appropriately sized homes that match how people actually live, especially singles, couples, and small families who don't need (or can't afford) a 2,500 SF home.

Attached Units: Sharing Walls Saves Space & Money

Duplexes, townhouses, and rowhouses represent a more efficient use of land. By sharing walls, we:

Minimize the need for additional setbacks between units

Increase the overall number of homes that can fit on a lot

Reduce per-unit construction costs through shared infrastructure

Create a traditional neighborhood character that many communities value

Lite Parked: Rethinking Parking Requirements

Parking requirements quietly kill housing affordability. Here's how:

Direct costs: Parking spaces are expensive to build. Surface parking typically costs $5,000-$10,000 per space, while structured parking can run $25,000-$50,000 per space. Please do not even ask us about the costs of underground spaces. These costs get passed directly to residents through higher rents or purchase prices.

Indirect costs: Parking requirements consume valuable land that could be used for housing. They increase impervious surface area (requiring more stormwater infrastructure), push buildings farther apart (increasing walkability distances and utility runs), and often mandate parking that sits empty most of the time.

Reducing parking requirements is a critical enabler to flourishing housing. We provide incremental ordinance strategies to do this through our sister company, Inc Codes.

In the Right Places: Maximize the Infrastructure that is Already There

Context matters: where a project is built also plays a major role in its attainability. Multiple, smaller units on a ‘single’ lot is much more contextually appropriate in older communities where this type of housing is already woven into the neighborhoods.

Building a single 600 SF cottage on a large lot misses the point. Older neighborhoods typically have the right characteristics to support this infill housing; on-street parking is more typical, alleys might be available, and established goods and services are typically located closer to homes.

Home Ownership Sells: Feed Politicians What They Eat

We find that politicians often have an easier time gathering support for home ownership in their communities. While we care deeply about inclusive rental options, we will take housing choice wins where we can get them. People often do not realize that America subsidizes homeownership at the federal level via FHA, 30 year mortgages. As a result, raising long-term capital to provide build-to-hold rental housing is a bigger lift than building to sell. Additionally, most local builders are geared to build homes to sell.

Small-format IRC housing can also be easily used for rental, but IBC missing middle buildings do not have an easy home ownership pathway. Calibrating development options with existing financial ecosystems to maximize attainability and often creates (slightly) less angst amongst local homeowners relative to new rental communities.

IV: WHAT POLICY MAKERS NEED TO KNOW

Critical Policy Implications of building codes:

Small multifamily buildings face disproportionate costs

A fourplex is much closer in size, scale and complexity to a duplex than it is to a 200 unit apartment building, but it costs significantly more to build under IBC requirements. This means these fixed costs must be spread across a much smaller number of units. For example, a sprinkler system has to have a tap in the street, meter, backflow preventer, and riser before you ever run pipes to individual units. This can easily run $10K-$20K. This is a minimal cost spread across 100 units, but substantial when applied to a triplex. This discourages the exact type of modest, neighborhood-scale housing many communities need.

Zoning and building codes should work together

If your zoning allows fourplexes but your building code makes them prohibitively expensive, you haven't effectively enabled that housing type. Consider whether zoning code modifications or state-level reforms could help. We also have ready to go traditional neighborhood zoning districts ready to go at Inc Codes.

Incremental development gets squeezed out

Small-scale developers and local builders typically work under the IRC whenever possible. Larger developers with access to capital are oftentimes the only ones who can afford to build to IBC compliance. This is due to the high cost of IBC’s requirements for specialized workers. An IBC requirement is also only feasible at larger project sizes which often clash with the existing scale of the neighborhood.

Consider advocating for state-level reforms

Tennessee and North Carolina have now permitted fourplexes to be permitted under IRC if all unit separations are two-hour fire separated, no sprinklers required. The added fire rating adds substantial costs that often are nearly equal to the initial installation cost of fire sprinklers, but does provide longer term savings by not requiring sprinkler monitoring. Ohio’s building code previously had a more rational set of requirements for small format multifamily housing. Buildings were limited to two-stories, stairwells had to be separated by two-hour ratings, but individual unit separations were only one-hour. This was a much more balanced policy for right sizing smaller missing middle buildings.

V: CONCLUSION | THE MISSING MIDDLE OPPORTUNITY

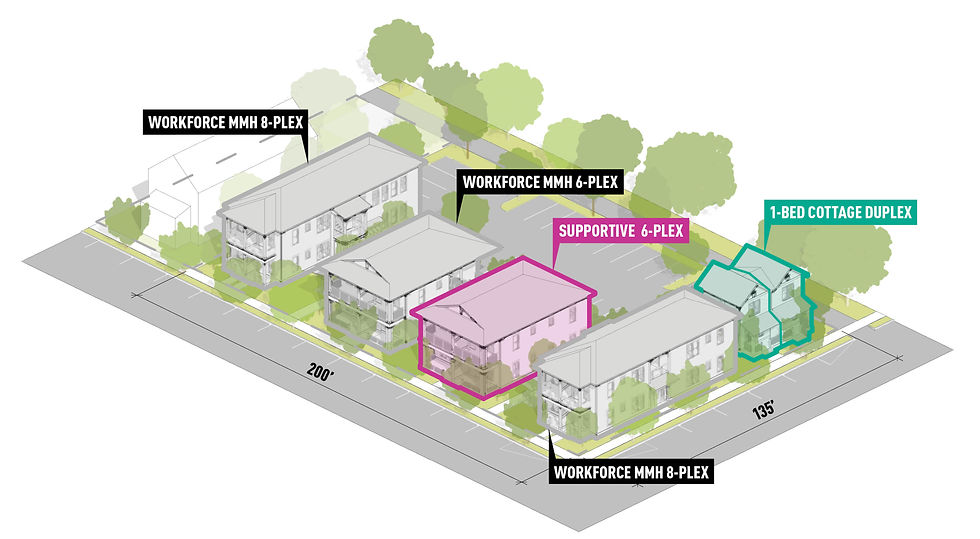

What Missing Middle IRC Housing Looks Like

This housing type is ideal for creating housing as well as achieving community and political approval.

Attainable IRC Missing Middle Housing:

Leverages existing infrastructure investments to support walkable or potentially walkable neighborhoods

Can be delivered at a price more viable for struggling communities

Provides homes at a scale and look that is compatible with traditional development patterns

Can be built by local developers and contractors

Provides fee-simple ownership options

Can be more easily financed by local builders and local buyers

The Local Path Forward

Focus on the details

We would love to see an influx of smaller format missing middle buildings be part of the housing solution. Some progressive cities have legalized fourplexes in their zoning, but wonder why so few get built. Projects that are allowed by right often are impossible financially due to the costs that come with building code compliance. It is imperative that policy makers and developers align policy creation with an understanding of building codes to maximize the creation of attainable housing.

For example: Reducing minimum lot sizes while providing fee-simple housing choices is a local policy that can move attainable housing forward. This can be an effective two-part strategy that creates more attainable housing choices while pushing for state-level legalization of fourplexes under IRC.

The Incremental Development Alliance was founded specifically to assist small scale developers with understanding the process of how to implement infill and incremental change in their community. This work allows for fewer large scale, unattainable, developments, and more context sensitive, impact-driven homes.

We have been faculty with the Incremental Development Alliance for a decade, teaching the fundamentals of infill development to small developers and municipalities. In 2023, we founded Inc Codes, a company aimed at right-sizing regulations for small and mid-size communities.

How State Level Action Can Help

Most states restrict building code modifications to state boards. This means that any fourplex building code reform must be tackled at the state level. We also see that most housing challenges are regional in nature. As such, there is a critical role for states to play in limiting the types of housing that cities are allowed to ban. Two-family housing, accessory dwelling units, and fourplexes were considered typical and acceptable housing options in neighborhoods built 100 years ago. These were practical, attainable, and unsubsidized. State level policies can and should tackle minimum lot size requirements, lot subdivision reform, as well as permitting right-sized missing middle buildings under the IRC. Groups like the Mercatus Institute and Sightline Institute (provide links) are providing great summaries of recently passed legislation from across the country.

The Bottom Line

Creating attainable housing isn't about choosing between affordability and quality, or between growth and neighborhood character. It's about removing unnecessary barriers, in both zoning codes and building codes, that make it harder and more expensive to build the types of vibrant, inclusive, and lasting housing our communities need.

By understanding the practical differences between IRC and IBC construction, and by aligning your zoning policies with your housing goals, you can help unlock significantly more housing opportunities in your community. The tools are already available- it's just a matter of using them strategically. Let’s get going.

For the downloadable version of this blog, see here.

Comments